As more and more countries are turning to Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) projects to create clean energy and mitigate climate change, it is important to understand how different biomass feedstocks influence the design and cost of carbon capture plants and, ultimately the levelized cost of capture (LCOC) of such plants.

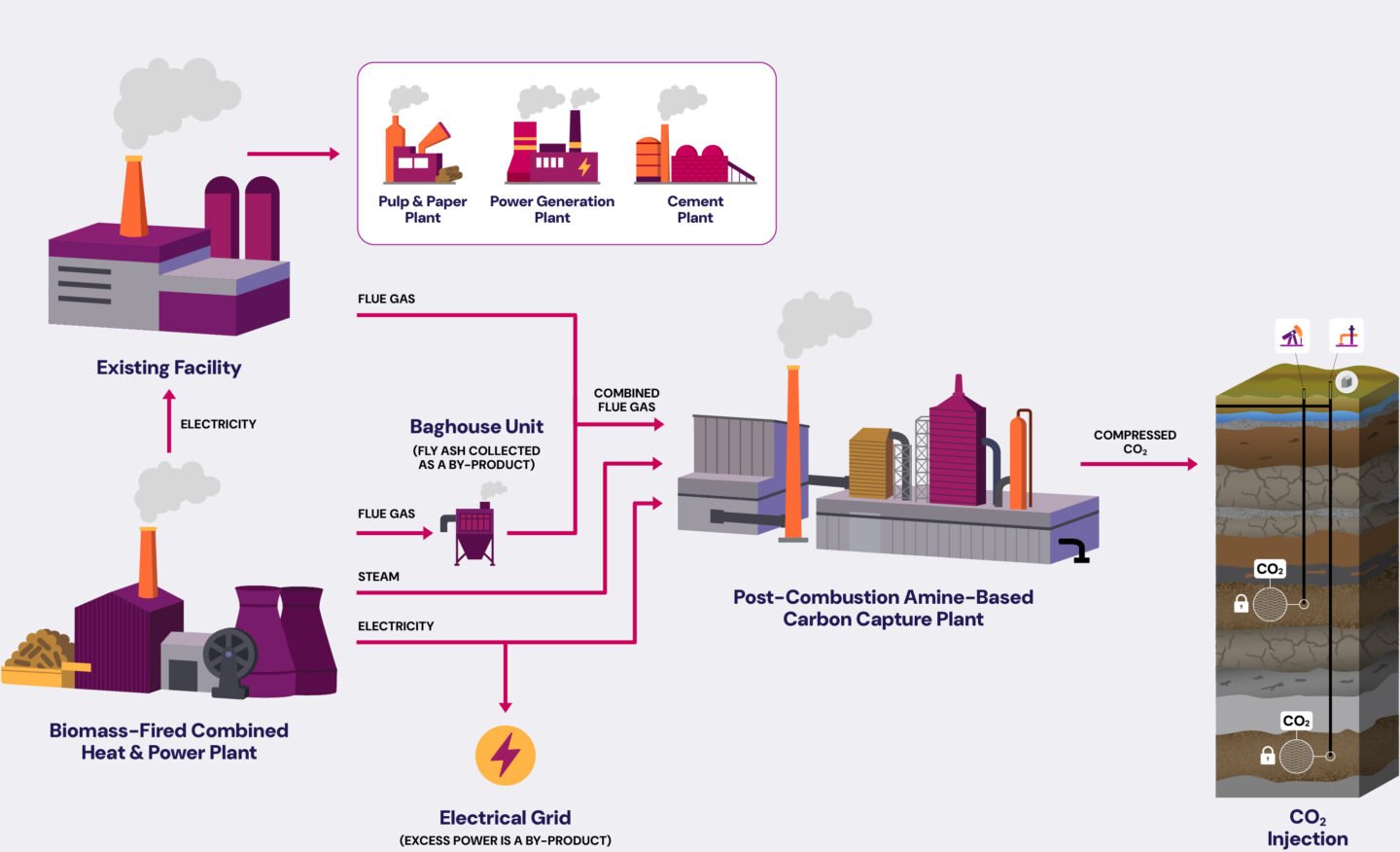

As discussed in BECCS 101- Turning Biomass and Waste into Clean Energy, BECCS generates energy using biomass feedstock (i.e. forestry residues, agricultural byproducts, dedicated energy crops, and the biogenic waste used in Energy-from-Waste facilities) while capturing and permanently storing the resulting CO2 emissions underground. As biomass absorbs CO2 from the atmosphere during its growth, this process achieves negative emissions, making BECCS a key tool for reaching global net-zero climate goals. With Canada’s vast supply of sustainably sourced biomass and proven CO2 storage capacity, understanding how biomass can be incorporated into post-combustion amine-based carbon capture plants has many advantages.

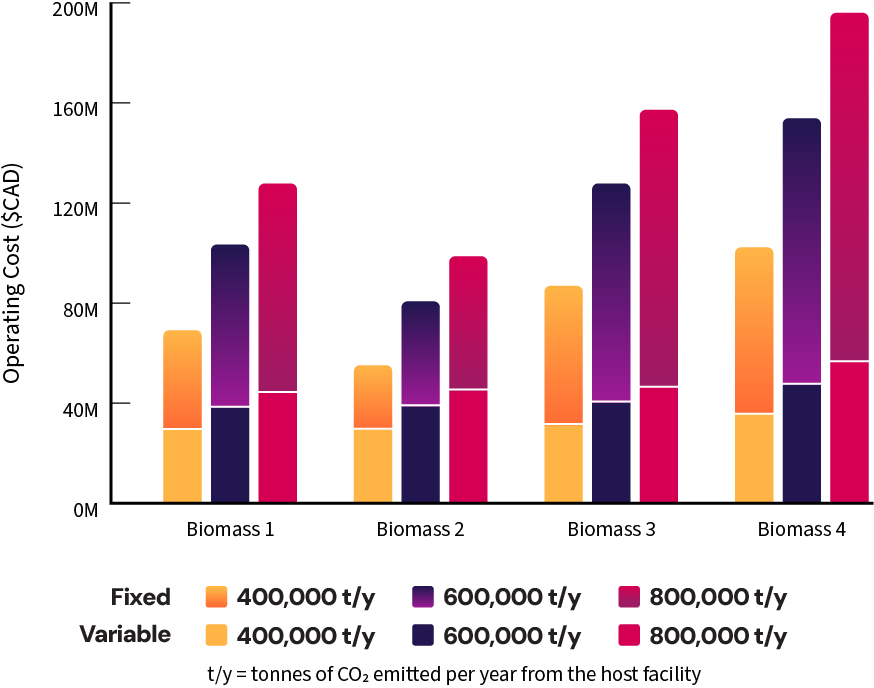

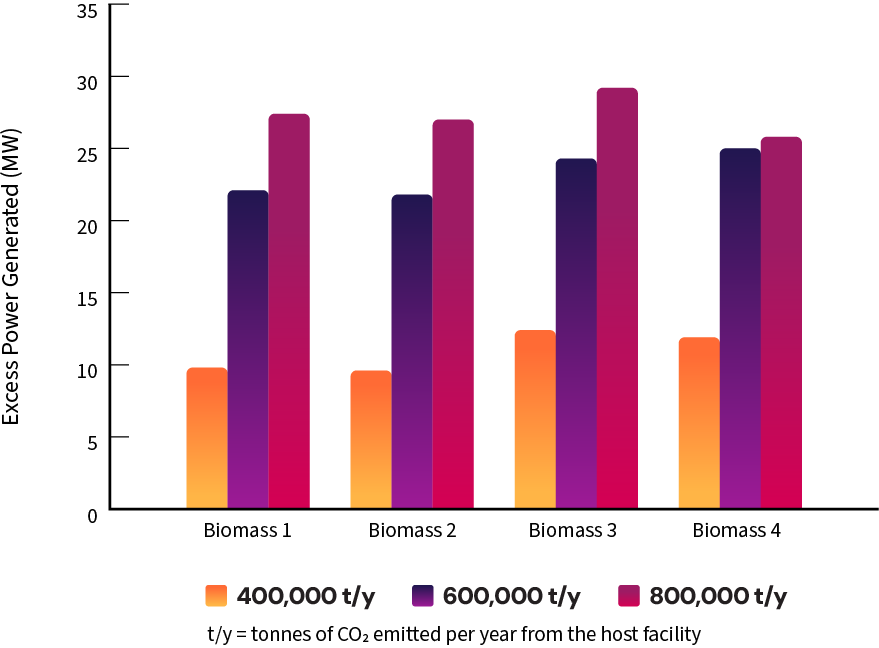

Post-combustion carbon capture systems using amine-based solvents require substantial energy to operate, contributing significantly to the overall cost of CO2 capture. One potential way to improve project economics is by incorporating a combined heat and power (CHP) plant. CHP systems can supply both the steam and power needed to operate the capture plant, helping to reduce energy costs and improve the project’s overall efficiency. Typically, a CHP plant produces more electricity than is required to operate the carbon capture plant and supporting equipment. This surplus, known as “excess power”, can often be sold to the grid, generating potential revenue, or used on-site by the existing facility to reduce its reliance on purchased electricity.

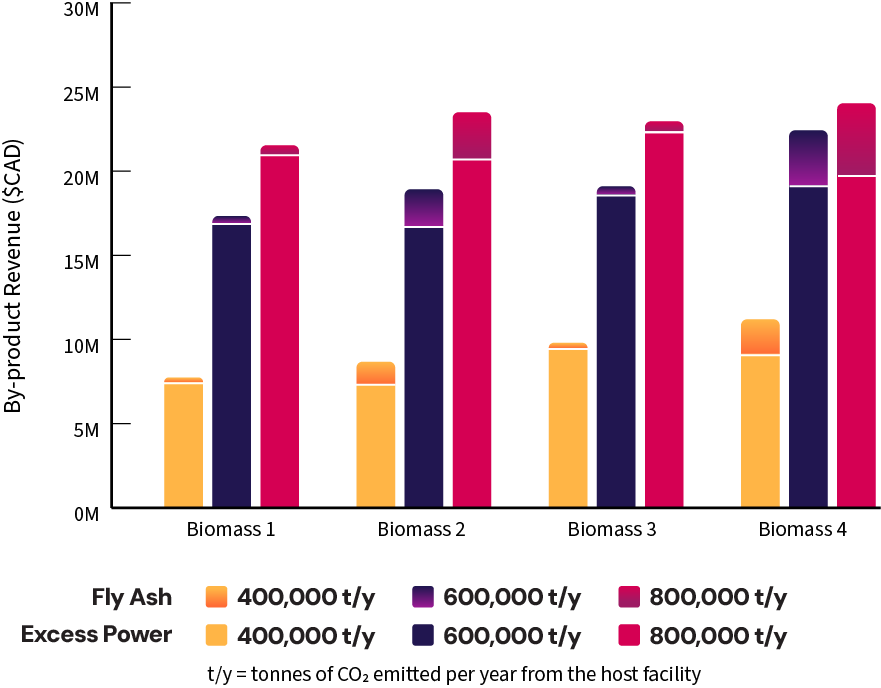

While fossil fuels like natural gas have traditionally powered CHP plants, a net-zero future will require more clean and reliable power sources. By switching to a sustainably sourced biomass to power the CHP plant, it enables the generation of low carbon or even negative emissions electricity, while also permanently removing CO2 from the atmosphere (i.e. enabling the reduction of overall emissions). In addition to producing excess clean power, another by-product revenue stream, although modest in nature, is fly ash, which can be sold for agriculture applications like soil amendment to improve pH and nutrient levels.

Explore the diagram below to see how it works in practice.